May 17, 2023

by Britt Robson, Bandcamp

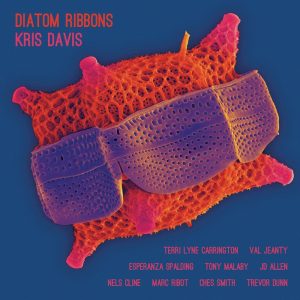

In 2019, pianist Kris Davis released the debut album from her group Diatom Ribbons, an ambitious, original project that was extraordinary for both its reach and its grasp. It was a propitious year for Davis, who is now in her early 40s. She had just received nonprofit status for her label, Pyroclastic Records, the imprint that had released her music over the previous three years, and was now equipped to showcase other kindred spirits in her orbit. She had also been named to the faculty of the newly created Institute for Jazz and Gender Justice at Berklee College of Music in Boston. And Diatom Ribbons was named album of the year by both the New York Times and NPR Jazz Critics Poll.

A year later, the Jazz Journalist Association would hail Davis as both Pianist and Composer of the Year—the latter especially significant, since she first made her mark in settings that prioritized free improvisation over composition.

In short, Kris Davis is a powerhouse and a polymath who never stopped moving forward. When I saw Diatom Ribbons in concert in March—preceded by an extended set of mostly spontaneous piano duets between Davis and Craig Taborn—the band had evolved into a different, but equally compelling, beast, mixing original compositions with songs by Ronald Shannon Jackson, Geri Allen, and Wayne Shorter, turntablist Val Jeanty again punctuating her and Davis’s electronics with vocal samples of the composer or other relevant audio.

A week after that performance, we caught up with Davis to discuss the ways her many pursuits—label founder, teacher, pianist, and composer—are in fact change agents for greater cultural awareness and an expanding creative community.

When you launched Pyroclastic Records in 2016, you were much less renowned than you are now. Why did you decide to take such a bold move?

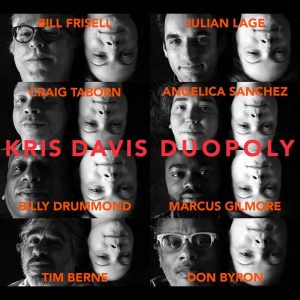

In 2016 I put out a record, Duopoly, that was funded by a foundation that supports arts. Since I owned the album outright, it didn’t make sense to shop it to other labels I was working with. So I decided to create a space that would be a platform to carry my music and eventually extend it to other artists I had worked with, or who were a part of the creative music community in Brooklyn.

I reached out to the VLA [Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts] in New York and got some guidance and took some classes on how to set up a nonprofit. I talked to other jazz artists who created labels, people like John Zorn and Dave Douglas. The not-for-profit status came through in 2019 and allowed me to grow the label enough to put out six albums per year.

Sounds like a non-traditional set up. What is the business relationship between you and the Pyroclastic artists?

Because we have not-for-profit status, we have a board and organizations can donate to the label each year for our basic funds and expenses. Beyond that, if we make any kind of profit from the label, it just goes back into supporting the artists and that’s kind of how it operates.

When it comes to what the label releases, for the most part, artists are sending in albums that are fully completed. We do a couple every year where we give artists some funds to record and make an album. But in general, we are getting such great projects that are already recorded that we are going that route.

In terms of what we provide for the artists, usually we’ll do the mastering if needed, plus the printing and then the PR—which is a really the strong benefit of the label; they get to work with a great publicist for a couple of months when the album comes out.

Now that there are so many artists, it is becoming a bigger umbrella for certain kinds of musical and cultural adventures—creative music that is noncommercial. It’s starting to create a following.

Along with Pyroclastic and your own flourishing musical career, you’re also teaching at the Institute for Jazz and Gender Justice at Berklee. That came about because of a friendship with drummer Terri Lynne Carrington that began as an email exchange over your mutual admiration, right?

Yeah, it was shortly after Geri Allen passed away in 2017. Terri organized quite a few tribute concerts for Geri and thought that I would be a good person to play. At the same time, she was starting the Institute at Berklee and asked if I would be interested in joining. I accepted the position in 2018 and then I commuted up to Boston [from New York] for seven months and then the pandemic happened. I taught online from my house for a year and a half, then I moved up to Boston last summer to essentially be more connected to the community up here.

I saw that one of your duties, in fact maybe your primary duty, is devising programs that seek to address or surround or offer perspective on gender issues in music. How has that evolved?

We are institution-building as we go, so we haven’t found the answers yet, just the will and the desire to send along a message. We have had quite a few guest artists come to speak about their experiences both in and out of the music world. [Pianist] Fred Hersch came and spoke about being gay and living with AIDS, and his activism; Angela Davis came and spoke; [photographer] Carrie Mae Weems came. Then it becomes conversational, as the students ask questions around gender, in terms of how they navigated certain things in their own careers.

Also, most of the way the Institute runs is that we teach in ensembles. And so Terri and I set up the ensembles so that is no more than 50% of any [gender or binary designation] in the ensemble. It creates this artificial experience of the diverse bands, which isn’t always going to be the case when performing outside the Institute, but we wanted to give the students an opportunity to experience what that felt like, and they all notice a difference.

What is that difference?

There are a couple of ways to answer that. When I was studying more traditional forms of jazz, there were guardrails about what jazz is or isn’t. And if you didn’t adhere to those rules, you couldn’t be part of the club, so to speak. Like playing “Cherokee” at 260 beats per minute, or going to a jam session that becomes a cutting session and being told you are not good enough and to get off the stage. When I was coming up, I tried to adhere to those things, but a lot of it didn’t resonate with me.

And so when I moved into more free improvisation, with no composition, I found there was a lot more diversity in that world, especially in gender. I found that in working with women there was more of a desire to collaborate, versus following a form created by a leader and having their vision being what was primarily being represented. And there were men who wanted less tradition and more collaboration in their music too. I think it is all beginning to trickle together in a good way, so that people can ultimately be their authentic selves; be creators and collaborators and not have to change their goals.

I love that you speak of diversity in terms of approach and style and how that gets mixed in with race and gender. That holistic approach and organic diversity is inescapable in the music of Diatom Ribbons—both in the record you made, and when I saw the group in concert back in March. Intentionally or unintentionally, the music seems to be a real embodiment of that diverse blend of style, lifestyle, and cultural awareness.

Yeah, I think that’s true, although I don’t think it is something I set out to do. I have always liked people with different experiences from me so that we all have something different to bring to the table. And certainly at Berklee our students are coming from all over the world, and they are playing an oud, or a gayageum—which is an instrument from Korea—and other instruments that are traditional to them, but not to us. And they are frequently using different tones—not the 12-tone system that is in Western music. But people also want to be involved in improvisation. And if we want music to continue to grow and evolve, we have to be inclusive about these other ways of thinking about music.

That curiosity is in your music. In concert, I was tickled to watch you play a grand piano in front of you, as well as a much smaller piano on your left and an EFX box on top of the smaller piano, and then to hear the music enveloping and folding into itself like an origami-type situation. It makes me wonder: If you had been able to “join the club” when you were coming up, that music might have come, but maybe not to the flowering it is now.

In some ways, I do feel like it has come full circle, because now I’m engaging in more traditional forms again, like playing tunes with changes and over more set forms. But I’m coming at it from a different mentality, having gone through the process of free improvisation and non-traditional ways of thinking about it.

I want to make the music and explore. The whole thing about jazz is that it is the only music where the audience is really meant to be part of the process of making it and discovering what is possible as it happens. When I hook up those different keyboards, I am experimenting, the band is experimenting, and the audience is watching the experiment unfold. That is unlike pop music or classical music, which are very polished and planned. It is a really unique experience that I want to pass on to the audience and to my students.

It also feels like that type of collaboration and exploration is where all the different aspects of your life converge—the record label founder for unorthodox creative music, the non-traditional teacher looking through the lens of jazz and gender, and, at the root, the curious, improvising musician. I read a quote from you that said, “Risk-taking is a comfortable space for me.” You are engaged in different ways to expand yourself and bring in other experiences that are a part of diversity when you see the chance. And it seems like you are maximizing those opportunities right now.

Yeah, exactly. If the music starts to feel too comfortable, that’s when I start to feel uncomfortable. Like we played a show a week after you saw us and we had to mix it up and instigate some changes; we had to relate to the tunes we were playing in a different way and not have the tunes dictate how we should be playing.

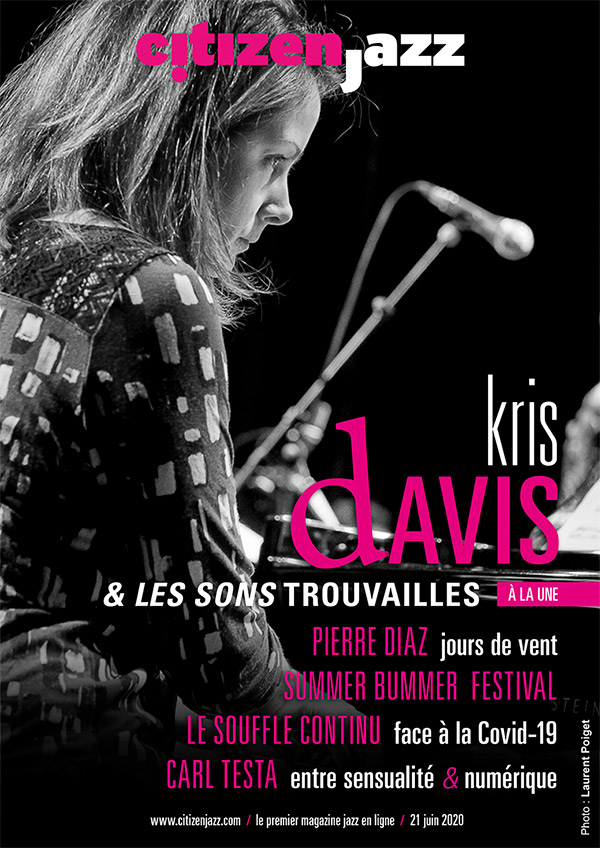

Jun 21, 2020

by Matthieu Jouan – Citizen Jazz

Ms. Davis is a calm and wise person who, despite her double award for Best Composer / Pianist in the annual North American Jazz Journalist’s Award, keeps her feet firmly on the ground. Teacher at Berklee College of Music, commissioned artist at the Monheim Triennale (postponed in 2021), active member of Terry Linn Carington’s or Ingrid Laubrock’s bands, she continues to be interested in others, to care, to share, to transmit.

In addition to her group Diatom Ribbons, which brings together two different musical universes she has worked with and which has been acclaimed by international critics, Kris Davis is also at the piano in an amazing quartet, bringing together the Norwegians Øyvind Skarbø, Ole Morten Vågan and the Swede Fredrik Ljungkvist. Finally, this year without a performance or a concert, is still a year of success, since a magnificent duo with his regular playing partner, the German and New York saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock, has been released.

Kris Davis © Tim Dickeson

– Where do you come from, musically and / or personally?

I grew up in Calgary, Alberta, Canada and started playing the piano at the age of 6. I studied classical piano until I was 13 and then joined the high school jazz group. Shortly after, I decided that I wanted to become a professional jazz pianist. I studied the jazz tradition for many years, I did a lot of concerts playing jazz standards, and I finally landed on the improvised music scene when I moved to New York in 2001.

– You have just won the prize for the best composer and the best pianist of the year 2020 awarded by the Jazz Journalists Association. What does it bring you? What do you think ?

I am truly honored to have been elected jazz composer and pianist of the year by the Association of Jazz Journalists. The critics are passionate and knowledgeable listeners of this art form and to be recognized as an artist who has an impact as a composer and pianist of jazz is simply breathtaking and it is a confirmation. I hope that many opportunities will arise from this award and that I will be able to continue to create and present new works that both appeal to and inspire the public.

– You have also been selected for the Monheim Triennale, which was postponed due to confinement. How did you experience this period of confinement? What do the next months look like for you professionally?

For many artists, including myself, confinement has been a blow to my work. I was to play for the first time as a leader at Village Vanguard in April, with the group from my new album Diatom Ribbons . I also had to perform at Canadian, European and American jazz festivals this summer with Diatom Ribbons. All of this was canceled or postponed to 2021.

In addition to these dates as a leader, it was also planned that I would present a silent film project in collaboration with the filmmaker Mimi Chakarova at the Boulez Saal in Berlin in April and at the Monheim Triennale in July. I also canceled several tours for the Charlie Parker project at 100 , directed byTerri Lyne Carrington and Rudesh Mahanthappa . Many of these dates have been postponed to 2021 or canceled.

I HAVE ALWAYS HATED HAVING MY PICTURE TAKEN AND THAT IS WHY I DECIDED VERY EARLY TO DOCUMENT CERTAIN MOMENTS BY SOUND RATHER THAN IMAGES.

Since confinement, I have spent the past few months relaxing and spending time with my family. My son is in elementary school and I spend half the day teaching him at home and the other half practicing a little and doing exercises. I struggled to be creative during this time, so I focused on maintaining my technique by practicing classical music and applying my creativity to other activities, like cooking!

– You have participated in many exciting projects in the past two years. What motivates you so much in your artistic choices?

I am motivated by a moment and the experiences of that moment, what I learn, who I work with, what I listen to and what happens in my inner and outer world. I have always hated having my picture taken and that is why I decided very early to document certain moments by sound rather than images.

I have practically recorded one album per year since I moved to New York and I consider that these recordings are only testimonies of a certain period. Since 2018, my collaborations have grown considerably and my musical life took a major turn when Terri Lyne Carrington asked me to play with her in 2018. I have always been a fan of her game and when she asked me playing with his group in Taipei, I was really looking forward to where it could lead. Shortly after this concert, Geri Allen died and Terri asked me if I would like to play a series of concerts in her honor.

I didn’t know Geri’s music very well, but I saw it as an opportunity to learn more about her and her music. We played his compositions – studying the scores and playing the music is really the best way to get to know any work. Terri felt that there was a connection between Geri’s play and mine because both were versed in jazz as well as avant-garde and shared similar influences, from Herbie Hancock to Cecil Taylor .

During this period, I asked Terri and Val Jeanty , the DJ who participated in the concerts in honor of Geri, to play an improvised concert with me during my week at Stone in New York. It was a memorable concert, Terri’s first improvised concert in fact. After that, I decided to make an album combining this new team with longtime collaborators, such as Tony Malaby and Trevor Dunn . The result was my last album Diatom Ribbons .

IT IS IMPORTANT TO DISCUSS GENDER ISSUES IN JAZZ, BECAUSE THIS IS HOW PEOPLE BECOME AWARE OF THESE ISSUES AND THAT PROGRESSIVE CHANGES TAKE PLACE.

In addition to this work, Terri offered me a position at Berklee, where she teaches, in her new Institute for Jazz and Gender Justice . I started practicing at Berklee in September where I teach with one group on free improvisation and with another on contemporary composition. We also receive many guests every semester who discuss issues related to gender equality and inclusion in jazz.

– It’s really interesting. To what extent have you evolved on gender issues in music and jazz?

This is a question that is often addressed in interviews and in education, an area in which I am very involved. I think it is important to discuss gender issues in jazz, because that is how people become aware of these issues and that progressive change takes place. In my work, I focus on discussing gender equality with young musicians, because they are the ones who will ultimately contribute to the paradigm shift.

– Have you experienced situations concerning gender issues in your life as a musician? And now has that changed?

Of course, there is an increased awareness of gender issues, not just in music but in all areas. I think progress has been made, but again I am focusing on the younger generation to raise awareness of these issues, as I truly believe that they are the ones who will have a significant impact on change.

– You play very creative and improvised music and jazz journalists use words to describe it, words which do not necessarily speak of music but of atmosphere. Do you read the reviews? How do you find the journalistic approach to your work?

I read reviews of my albums – I always appreciate people who take the time to listen and write about their experiences with my music. In general, I find that the journalists have always supported the work.

I once heard critic Bill Cole tell a story about Herbie Hancock : Bill had criticized a new album that Herbie had released in the 60s and had written a negative review. Herbie then called Bill and asked him why he wrote a negative review. Herbie explained to Bill how difficult it is to get by as a musician and that such a scathing criticism would make it difficult for him to sell records and would make him lose part of his income. It really hit Bill and he stopped being critical after that, realizing that he didn’t want to make a negative contribution to anyone’s music career because he knew it was a hard way to go.

I THINK INGRID LAUBROCK IS ONE OF THE MOST UNDERRATED COMPOSERS OF OUR TIME

I do not know if this thought affects other critics, but I think there is an awareness of the difficulty for artists to continue to release albums, especially in our time. And if a reviewer doesn’t like it, he / she always has the option of not evaluating the project. I feel very privileged by the fact that over the years, critics have supported my work.

– You have been working for a long time with the saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock in different orchestral contexts and you are now releasing a duet called Blood Moon . What do you share musically with her?

Ingrid and I share the same musical temperament. I personally think that Ingrid Laubrock is one of the most underrated composers of our time.

– Why do you say that?

Because I believe that it has not received the recognition that should benefit a person who invented his own language and did a colossal job.

I learned so much from her: she absolutely has her own voice and a unique language as an improviser and composer. We first played in my living room 12 years ago with Tyshawn Soreyand there was an instant musical alchemy. I then knew that she would be an important musical collaborator. Since then, we have worked together in many contexts: she played in my group Capricorn Climber, I played in her group Anti-house and her orchestra project, and we started to play in trio with Tyshawn Sorey, under the name of Paradoxical Frog.

– You work, in particular on this duo, the composition and the microtonal approach of the instrument. What technique do you use for this?

I don’t really know much about microtonal approaches – I’m mostly interested in the piano’s response to microtones and I’m trying to figure out how to frame or accompany them on an instrument that can’t instantly go into microtones (but who can if the piano is tuned this way, like on a recording made recently with Hafez Modirzadeh ).

Pic Tim Dickeson 27-10-2017 Kris Davis (Piano) Billy Drummond (Drums)

– In Blood Moon , there are slippery sounds and strange sound layers which are not usual with a duo of saxophones… where does it come from?

Ingrid uses microtones in her compositions, as we can hear in her song “Blood Moon”. I think she wrote this piece because she always takes into account the players for whom she writes: we have experienced this kind of sound (microtones on the saxophone with the piano) for many years when we improvise, by finding a means of framing the microtones when we are accompanied by the piano and something that resembles our unique language as a duet.

– On the technical level, what do you remember from your meeting with Benoît Delbecq?

I continue to use the piano technique prepared in my work – I love the variety of textures it allows and Benoît is the person who made me discover this possibility (with John Cage).

I also like the fact that it creates found or unexpected sounds.

“SOUND FINDS” HAVE BECOME IMPORTANT IN MY CONCEPTUAL APPROACH AS IMPROVISER

Certain forms which fall under the hand of the pianist have a certain sound, for example, when you place your hand in the C position and the fingers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 play the notes C, D, E, F, ground. If you prepare one or two of these notes that I just mentioned, you suddenly add an unknown to the gesture depending on the materials you use.

This can produce a percussive sound, a harmonic that gives the impression that you are jumping an octave up for that note.

The addition of this unknown element when I improvise corresponds to my conceptual approach to improvisation in the sense that I can make music from anything, and discover music in this “sound find” is really what improvisation is.

– It’s almost like improvising in improvisation! You are talking about the essence of this music: surprise, the unknown, the unexpected, the disconcerting. Do you agree ?

Yes. As an improviser, I always try to really improvise, to do something that I have never done before. As an experienced improviser, it becomes more and more difficult because you end up developing a lexicon of ideas and sounds. It is important to develop your own language, but there is a delicate balance between personal language and the use of language that is really improvisational in nature. This is why “sound finds” have become important in my conceptual approach to improvisation.

– Do you think there is a community of spirit, a sorority between Mary Halvorson, Ingrid Laubrock and you? There are many bridges between the three of you.

Mary, Ingrid and I have been playing together for 10 years now in various projects, and the three of us work together in Ingrid’s group, Anti-House. We all come from different backgrounds and experiences, but yes, I think we share a community of spirit, as composers, improvisers, craftswomen and risk takers. There is a feeling of mutual admiration and support between the three of us, which is both refreshing and comforting. I think it takes a while to find your “people”, especially in New York. I was in New York for 8 years before meeting Ingrid and Mary Halvorsonand when I started working with them, it was a trigger. I felt a sense of acceptance and support that continues today, even if we play with other people and develop new projects.

– What music do you listen to for fun, at home or on the go?

I listen to a wide range of music, from Andrew Hill to Anderson Paak. From Boulez to Cecil Taylor, from Scarlatti to the birds of the Amazon rainforest. When you asked if music works as a universal language, I think it absolutely is IF your ears and your mind are open to it. Organized sound is universal – even random sounds are universal because we, as listeners, have the ability to organize it in our mind. John Cage talks a lot about this.

AMERICA IS FULL OF WONDERFUL, PASSIONATE, INTELLIGENT, CREATIVE AND GENEROUS PEOPLE. PEOPLE WITH HEART AND COMMON SENSE.

– As we speak, there is this pandemic going on – and New York has been hit hard – and also (again) protests in the United States against the overtly racist policies of Trump and his cronies. What is your position as a citizen? Are you afraid of the future?

My heart is broken. Disappointed.

America is broken. It has been for a long time.

All these terrible events only reveal the failure of the system. Racism. Misogyny. Lack of respect for all human life. Indifference to the health of our planet. I consider myself an optimistic person, but I have a lot of trouble keeping hope these days.

In my experience as a foreign national, America is full of wonderful, passionate, intelligent, creative and generous people. People with heart and common sense.

When I moved to New York 19 years ago, I knew I wanted to stay there for good. Since living in the United States, I have slowly learned for myself how deeply rooted racism is in American history and culture, especially as a jazz musician who works with many Blacks and Métis . I discovered that fundamental human rights are not respected in the United States.

Yes, it is indeed a dark period for the United States. I hope real and lasting change will eventually happen by lifting the veil on the ugliness that characterizes America.